Why provide training in personal safety for housing staff?

Dynamis has provide training in Personal Safety for housing and related teams all over the UK since 2006 when we first developed courses for Edinburgh City Council, subsequently rolling out to Peterborough City Council, Dundee City Council, London Borough of Hackney and for Housing Organisations all over the country.

In this article our staff writer and chief storyteller for Dynamis, Vanessa O'Dea talks to coach-trainer Alex Hunter about recent training we have provided for a Probation Housing Officer team who are facing the challenges of conflict and personal safety in their work.

Introduction to personal safety for housing staff

Vanessa:

Hi Alex, it’s great to talk with you today about some recent training you’ve been doing in Personal safety for Housing as part of the team. Who called Dynamis in to help and why?

Alex:

I’ve just finished one of our two day conflict and personal safety training course for Probation Housing Officers. These officers deal with people out on probation from prison, facilitating their housing needs. And they occupy a space in the middle between the Probation Service and the service user.

The Probation Housing Officer is not a Ministry of Justice job, unlike the Probation Service. Probation Housing Officers facilitate people coming back into the community after prison and having a safe place to live while they do that. It’s a challenging job in itself - and the challenges are increasing. The Probation Service is stretched, so it’s hard to provide enough individual care and attention to the service users. For this reason, and because service users often want to keep their contact with the probation service to a minimum, Probation Housing Officers find themselves bridging that gap more and more. This requires a more detailed and intense relationship with the service users.

For Housing teams, personal safety information is Safety

Vanessa:

Probation Housing Officers are having to do more and are expected to have more of a detailed knowledge because services are stretched at the moment. Is that right?

Alex:

Yes, that's exactly right. Probation Housing Officers look after service users in as many ways as they can, for example doing tasks like going shopping, organising access to food banks, looking at maintenance of properties. This is all part of their remit, but they are having to go further because often the service users want to have as little contact as possible with their Probation Officer - whether that's because they don't trust their probation officer or don't feel they get the service they want from them, or because they have tried to contact them and not had replies because the Probation Officer is so stretched.

That's one of the common stories I heard on this personal safety training course. Service users contact their Probation Officer, they get no reply. Then they contact their Probation Housing Officer and perhaps make requests that are outside of their duty of care - requests that are at the boundaries of it. For example, "I need to contact social services for this” or, “I need to contact the benefit office and I don't know how to do it." And so Probation Housing Officers have to provide signposts that would normally be a Probation Officer's role.

Another common story in the daily life of the Probation Housing Officers was arriving at sites where they've got conflict between service users, because they are living in the same building. For example, there was an article in the BBC last year where a man on probation in a multiple occupancy home stated to the Probation Service, "You need to get me back into prison or I will kill one of the other service users here." He’d let slip to others in the home that he was a child sex offender and he was saying, "I need to go back to prison for their safety and for my safety." So conflicts in multi-occupancy homes are very, very common.

Scenarios like this reveal a personal safety issue for housing staff: important information is not always shared by other organisations (for example the Ministry of Justice or mental health services) about the risks involved with a particular service user. Sometimes that can be because of data protection or patient confidentiality. Community-based staff can be going into a visit blind, not knowing if the service user has a violence marker against them, or if there are any specific violence warning markers - for example, females mustn't attend because they have a history of violence towards females. In addition they may not know if the service user has a particular medical condition (for example schizophrenia) that could elevate the risks.

Certainly with housing maintenance staff (which can be a tailored training course in itself), it's quite common for the risk indicators not to be known until after they've done the job. They make a risk assessment on arrival based on the information they have. Then they do the task, they come away from the task and then they're told, "That's meant to be a two-person job. There are violence markers there."

It can be both amusing and disturbing to hear housing staff tell stories about receiving new files for a service users that don’t contain all the relevant information on their previous offences and risks. They have to go digging for this information on their own, using Google and various news sites to determine what level of personal safety risk they may encounter on a visit.

VIDEO: A story about the importance of information sharing to keep community-based (and lone workers) safe.

So it is really important to explore this fully to develop personal safety for housing teams, and to help them identify what relevant questions they must ask prior to any visit, so they can be satisfied in themselves before they go into a situation that they have covered all the bases with regard to risk - for their own safety and protection. Where information is lacking, we help them understand processes around due diligence and encourage them to do the relevant research that will help them keep themselves and others safe. We want the organisation to address this issue - and whilst they are at work on that, our job as trainers is to help the team to develop the tools to deal with what is happening on the ground, right now, day after day in their roles.

It may be necessary for individual Officers to take this approach to ensuring their own safety as they do their jobs, but as an organisational approach (see this HSE video) to keeping people safe, it is really lacking. We challenge system leaders to review how sensitive information pertaining to service users is communicated and disseminated within and between organisations, so that the dignity and safety of staff is balanced proportionately alongside that of service users.

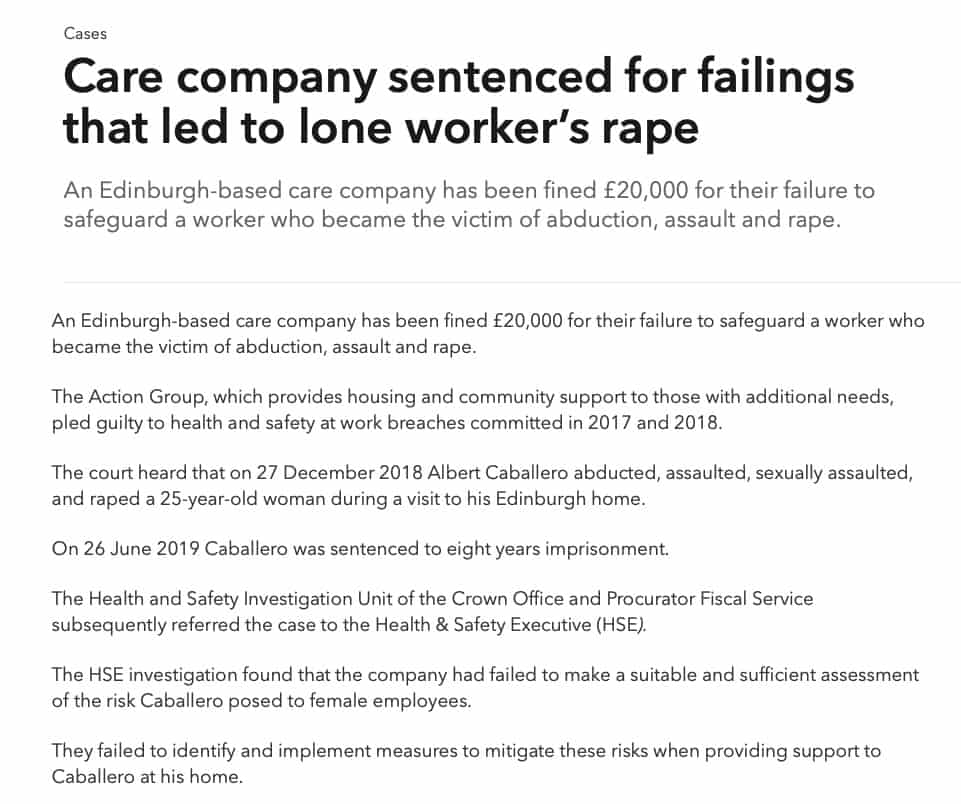

Costly examples of safety failures in personal safety for housing:

How much does Personal Safety Training Cost in Housing?

The first thing to say about this is that you should see the above examples of how much it costs to NOT have lone worker personal safety and conflict management training for your staff, if they are facing the risk of physical violence in their work. The attention from the Health and Safety Executive, and subsequent fines under section 2,3 and 7 of the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, can be eyewatering!

We estimate that the cost of professional and expert-led personal safety training with a qualified provider probably ranges from £1,000 to £1,500 per training day.

By our analysis, anything less than this level of investment would suggest that the provider is operating in the capacity of a sole-trader (a freelancer) and may not have the volume of business to independently sustain the research, medical risk assessments for breakaway techniques, accreditation standards, quality assurance and, let’s face it, the office management capacity to be a reliable, long-term safe pair of hands for your training budget.

If you face an adverse incident in your service, you will want to lean on a partner who has all of these things in place, and more.

Here are some considerations:

- what is the limit on class size for the stated day-rate? We have seen providers with maximum class sizes of 8, 12 or 16 for training. Sometimes you can pay per-learner for additional learners, sometimes if you go over the maximum, you need to book another full course!

- how many people can the class accommodate, maximum? You should consider the effects of group size on learning quality. The more people in the room per instructor, the greater the effect on learning, and vice-versa.

- is there a minimum number of learners needed for a class? If you have just a handful of learners, you might want to consider inviting a team from another service to join your training event, to mitigate against costs and to enhance the training day.

- what happens if I need to book more than one group of learners? Does the cost multiply in a straight line, or is there a sliding scale of costs once we have a programme rolling?

- how much does it cost to add another person to the class? Some providers might let you add learners at a per-person cost.

- does the provider charge VAT? VAT is a feature of doing business with bigger, more established providers. Smaller (sole-trader) providers may not charge VAT but may also be a riskier proposition.

- does the provider charge mileage expenses? Some providers will have a higher day rate but provide their training as an “all in” price. Others will have a base-price plus mileage. Both are legitimate (good personal safety trainers are in demand and travel A LOT!) but you might want clarity on what your costs are going to be in a Total Investment quote. Always ask for a total cost quotation or terms and conditions before confirming.

- does the provider need to charge overnight expenses for a travelling instructor? This is also a legitimate cost request which may be added to your invoice. Again, popular personal safety trainers travel a LOT and in order to keep them fresh, to provide great training for your team, a provider may have rules about travelling distances and overnight expenses which they should be happy to discuss with you and include (where needed) in your estimates.

In the end, you’re probably going to feel most comfortable with a provider who makes the investment model for your positive handling as transparent and reliable as possible, considering your needs.

How should Lone Workers assess personal safety risks?

Vanessa:

A significant issue for staff is around sharing information: lone workers don’t always have the information they need to effectively prepare for visits with service users and stay safe.

What are Housing Officers to do if they don’t have all the relevant information they need about a service user prior to a visit? How do they accurately assess the risks?

Alex:

Well, the simplest way to assess personal safety risk - and this applies to any situation where you're going to be public facing - is to ask ‘who, what, where, when, why.’ When you get to risk assessment, you want to know ‘what's the risk this service user poses to others?’ And ‘What's the risk they pose to me?’

To unpack this a bit more, understanding risk starts with Housing Officers being able to answer these questions:

What has the service user done in the past? Because previous violence is an indicator of future violence.

Is there a health or infection risk? We've just come out of COVID. So you'd expect people to be very hot on this one and aware of infection risks. But it’s important to know other ones too - if the service user has HIV, or Hep C for example. If the Housing Officer doesn't know and there is an incident, there can be infection transmission issues. And from the organisation’s perspective, if they're sending their staff in where there's an infection risk and Housing Officers are not made aware of that infection risk, the organisation is liable for that case occurring.

What physical risks does the environment pose? Most Housing Officers are aware of their housing stock and associated risks of the physical, built environment. But insert the human beings and things can change very quickly. If you've got a multiple occupancy house with four rooms, there are three service users already present and one service user is moving in, what kind of risks exist in that environment for both the new service user and the old ones? So it's about knowing the service users already in place and also gauging the environment and what those service users in place will do with it.

The most common, most concerning risk in thinking about personal safety for housing teams is knives. Anyone can go out and purchase a knife in a supermarket for a few pounds. One of the rules with regards to being in property is that knives stay in the kitchen, they're not in bedrooms, they're not in common areas. And then the Housing Officer arrives to do a check and there's a knife on the sofa, there's a knife on the bed, there's a knife on the bed stand.

In the training we looked at that as a specific scenario: you've arrived and there's clearly a weapon present. It's not in hand, but it's there. So how do you deal with that? Context is key - choices Housing Officers make always depends on the behaviour of the service user.

VIDEO: Why a history of violence is such an important issue for protecting lone workers and community-based teams.

How should Lone Workers Manage Conflict?

Vanessa:

So there's (1) the communication issue within and between agencies. Then there's (2) the assessment of the risks to self and to others, as well as the risks posed by the environment.

What are some of the things you taught the Housing Officers about how to manage an encounter with a service user who may be unpredictable or even dangerous? How are they to stay safe whilst out on the job?

Alex:

So in training we covered the importance of the initial risk assessment. The next area of focus was dealing with the initial encounter.

When Housing Officers knock on a service users door, they need to knock and then give space, otherwise they're inside two to three feet when the door opens. It sounds like common sense, but it’s not until folk practise this that they start to realise it's best for their safety not to stand in a doorway when the door is opened - because a service user with bad intent could open the door and grab them straight away.

Housing Officers should observe the service users’ behaviours in this first encounter and assess whether the behaviours match whatever negative condition the Housing Officer is there to address. They need to be very alive to this so they don't fall into traps. MICE is a helpful acronym here: someone who wants to groom another will Manipulate, Intimidate, Coerce and Exploit. We get learners evaluating behaviours against this metric in order to support decision making to keep themselves and others safe.

For example, one of the most common traps is when a service user is super friendly. We encourage learners to ask themselves: why are they behaving in this way? Why are they so extra polite? Is it because they are genuinely that kind of person? Or is it because there's a hidden agenda and a goal that behaviour is directed towards? If a service user has just come out of prison and is in accommodation where the toilet's flooded, they are not likely to be happy - they are more likely to be upset or concerned. If they are coming across super friendly, Housing Officers need to be wary. The service user is exhibiting a set of behaviours that doesn’t match the situation Housing Officers have come to fix.

And that's why the scenario-driven training came into its own during this training: learners ran these different behaviours for their colleagues and practiced analysing the situation in the moment, picking up on the behavioural cues and adjusting their responses accordingly. This could be the difference between them going home safely or there being an incident.

Alongside observing behavioural cues, we also taught how vital it is to listen to their instincts. We go into public spaces all the time and our instinct gives us a feeling. Most of the time it's either a neutral or a safe feeling. But if instinct fires the other way and gives a feeling of ‘This is not right, I shouldn't be here’, we need to respect that and have practised the best and safest response to that feeling - which is always pay attention to instinct, take it seriously and act on it to exit the situation. Look for an exit route and have a polite and respectful excuse ready to step out. The most common is, "I have to make a call." Or, "I have to do something on the tablet."

This guidance explains how to keep lone workers healthy and safe. It is for anyone who employs lone workers, or engages them as contractors etc, including self-employed people or those who work alone.

Lone workers face the same hazards at work as anyone else, but there is a greater risk of these hazards causing harm as they may not have anyone to help or support them if things go wrong.

What are the most challenging situations for lone worker personal safety?

Vanessa:

What did you teach about how Housing Officers should manage conflict between service users?

Alex:

Conflict between service users is another large area of the work for the Housing Officers I was training with. They get called to a property because two of their service users are causing each other problems and are arguing and/or fighting. And yes, the Housing Officers have to manage the property and the service users', health, safety and welfare, but they're not police officers. Their role is not to prevent crime, their role is to make an assessment on whether the police need to be called.

Now do they use that as an inhibitor to stop aggressive behaviour in these service users? As a negotiation tool it sounds like a threat, which is an issue. The debate we had on the training was at what point do Housing Officers bring calling the police into the conversation? If you bring it in too early, no room is left for any other options. But if it’s brought in too late, service users might be so aroused by that point that they don't even care about that consequence. You could say, “500 men are going to come and sort this out now,” and they wouldn't care because they're so emotional.

Once again scenario training was key. We spent time practising safe deescalations in situations like this. In some scenarios we made the decision to go to a consequence immediately, for everyone's safety. Get out, call the police, wait for them to arrive, facilitate police entry. Then essentially it's out of the Housing Officers hands and their focus is on looking after the property.

Vanessa:

Associated with the arguing and fighting - how should Housing Officers manage conflict with service users who are under the influence of drugs and/or alcohol?

Alex:

This is something Housing Officers have a lot of. For example, arriving at nine o'clock in the morning and the service user is under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

Although the context is rather different, the key question remains the same: what's the approach going to be which is both compassionate and focussed on maintaining the Housing Officers’ own safety first?

If they've got the relevant information about the risks posed by the service user, which we talked about in your earlier question, that gives them a chance to make a decision on whether they just back out and call an ambulance, call the police or call the probation service, depending on the context. Because it could be that there is a no alcohol or no drug use condition on the person's probation.

Vanessa:

What’s an appropriate response if Housing Officers find that service users have other people in the property with them?

Alex:

That's a very common problem - service users have just come out of prison and they invite people round. This can sometimes be against the rules of their probation and use of the property. So a Housing Officer knocks on the door and a stranger answers the door. Not their service user. And they have to deal with that situation.

That was an interesting one to run with in the conflict management scenario training. We covered a range of experiences. A common response was, “Oh, hi” - nice and pleasant - “You shouldn't be here. I'll give you 10 minutes if you just make your way and then I can talk to the service user.”

But in the past they've also experienced people who refuse to leave, so we also practised scenarios where things kept escalating and the priority of the Housing Officers shifted to keeping themselves safe while they deescalated, or got out of the building and then called for that help to come in.

Vanessa:

It seems that empathy is very much at the core of the Dynamis approach to conflict management. Offering the service user dignity and respect, by trying to see things through the eyes of a loved one. Trying to get into that perspective and using the Housing Officers’ own empathetic responses to refine and improve the training experience and the next run of the scenario. Is that about right?

Alex:

You're absolutely right, by getting them to repeat the exercise and look at it from different perspectives, they were empathising while they did the training. The more learners do that, the more repetitions they do, the more they are fostering the skill set for when they go out operationally.

Housing Officers are frequently in situations where they are experiencing high adrenaline, things are unpredictable and there are multiple points of information coming at them all at once.

Using scenario-based training to improve personal safety for housing workers.

Vanessa:

How did the Housing Officers respond to the Dynamis training model you explained above, in which they practised conflict and personal safety scenarios over and over again, with you introducing new variables as training progressed?

Alex:

A key part of our personal safety training is running a scenario until it comes to a successful conclusion. If you run a scenario and it fails, you can't stop there. You have to reset and run it until it succeeds. Getting to success is really important. We trainers have to be very clear, detailed and positive in our briefings so learners have some scope to play the part and are able run the scenario as effectively as possible.

Whilst some Housing Officers ran the scenario, they were observed by their other colleagues and were encouraged to give feedback during ‘hot debriefs’ at the end of each iteration of the scenario.

It was encouraging to see their confidence grow as they provided instant feedback to one another. First of all, they gave their impressions of the scenario as if they were a fly on the wall. Then they evaluated the scenario from a service user's perspective, before looking at it from a legal perspective and then from another alternative, personal safety perspective.

For example, I might say in the hot debrief, “What would you think of this interaction if you were the service user’s mum who had just observed this? What is she feeling right now?” The response could be, "Oh, well I was a bit harsh." And then a follow up question would encourage reflection and empathy: “Okay, in what way were you harsh? In what way might you appear to not be meeting that service user's needs, now there's a different bias on it?”

When Housing Officers evaluated scenarios from other perspectives, they were able to look at their own behaviours differently. They were more open to evaluating their own behaviours and they started to pick up on things they hadn’t noticed in the past.

This training approach is really helpful when many interactions are filmed. It’s common for service users to pull out their phones the minute Housing Officers arrive. They record the whole interaction, just in case there's something that happens they can use later. If Housing Officers are not aware of how they come across to different observers, that places them and the organisation open to all sorts of problems.

VIDEO: Five insights from our experience of teaching teams lone worker personal safety training.

What are the key personal safety lessons for lone workers?

Vanessa:

I'm interested to know any best moments or challenges on this conflict and personal safety training course. Were there any inspiring, surprising or challenging moments from your point of view as the trainer?

Alex:

It wouldn’t be as a result of this particular training course, but on every one or two day course for this organisation there was always a story about challenging circumstances where one person had been placed in a significant risk situation. They coped with it, dealt with it and came out safe. Typically they realised the risk level afterwards.

Since we’ve been doing this training with Housing Officers and emphasising risk management, the organisation don’t dispatch them on lone visits anymore; instead they are in pairs. So that's a win for everybody.

I always appreciate the honesty of learners about the risks they face in their work. On this training, two of the Housing Officers had been to a service user, a woman with a very violent history. She tried to murder another service user while they were there. The Housing Officers did what they could, but in the end they had to withdraw and hide in their car while the service user struck the car window with a blade. They were very afraid.

When they shared the story, the fascinating part was they started to talk about their behaviours. Once they were in the car with the windows rolled up and the blade was hitting the window, they had started to laugh. One of them asked, “It's really strange. Why did that happen?” This question opened the door to thinking about the role of adrenaline with the group and how it can affect our emotions and behaviours when in dangerous situations.

It also highlighted an important danger that Housing Officers and their employers need to guard against - it is possible to become conditioned to high risk and then deny risks while you're in a dangerous situation. It’s vital to consider the behaviours and look at your safety every time in every situation.

Vanessa:

What did the learners appreciate the most about the conflict and personal safety training? Did they comment on any particular aspects?

Alex:

Yes, the fluidity and choice within the training. Within the structure of scenario training, it’s really important learners have choice and are able to come up with the scenarios.

In the training the learners contributed one scenario each that they had actually experienced. They set the parameters for the briefing as accurately to real life as possible.

Once we’re working with actual events that have happened to learners, you've got something that can really tap into. They can step out of the scenario and observe it while someone else plays it out. They see how another colleague would have done it, and another, and another. If the colleague deals with the scenario in a similar way to them and there is a successful outcome, they feel validated. That's empowering. If they spot something someone does differently that leads to a different outcome, then they pick up on a way of developing their own methods of practice and get a new skill by watching one of their colleagues. Everyone supports the development of everyone else’s best practice. They really own the training - there are light bulb moments everywhere and they thrive as learners.

That’s so good to hear.

What are some quick-wins for organisations looking to keep lone workers safer?

Vanessa:

To close things off, what recommendations would you you make to this organisation or others like it following this conflict and personal safety training?

Alex:

The Housing Officers all drive similar coloured vehicles with consecutive number plates. When they arrive at a service user's house or in that area, they're in two cars. Same make, same color, consecutive number plates. Add to this that they make calls at odd hours, for example 11 o’clock at night. When they drive onto an estate or into an area, the first impression may not typically be, “That's the Housing Officers arriving.” The first impression could be, “That's the police.”

If it’s easy for service users to know the cars arriving are Housing Officers, there’s less of a risk. But if they don't, they're going to go to the first thought, which is, “The police are here.”

That has presented Housing Officers with problems - for example someone who's adrenalised because they think it’s the police at the door probably won't read the work I.D. badge that's around the Housing Officer’s neck to clarify who they are and which organisation they are with. The organisation have changed the colour of the Housing Officer’s lanyard which is fantastic.

When they were blue it was easier for service users to mistake them for police lanyards.

It's helping individuals and organisations identify these little things that make a difference that makes training for me.

Vanessa:

To finish up then Alex, the main recommendation I’m hearing is to pay attention to what we might describe as the ‘critical non-essentials’, for example the cars Housing Officers are driving; the lanyards they are wearing. Organisations should ask themselves how effective their Housing Officers are at putting themselves in the shoes of others, always reflecting on the response to the question, “How can this particular issue or event be perceived?”

Is that about right?

Alex:

Yes, the art of reflection. A favourite phrase of mine which I tend to use on every course is, “The small things. There's nothing bigger.”

Dynamis provides Lone Worker Personal Safety [link] and Conflict Management [link] training for organisations of all kinds who field staff working in the community.

Our thanks to Senior Coach-Trainer Alex Hunter for his insights!

If you would like Alex or another of our expert team [link] to help you improve the safety of your community-based workers in housing, social-care or other work (probation, utilities services [link], retail [link]) then by all means contact us.

start today

What areas of training do we cover?

Your team need to know how to identify and prevent conflict, but also how to manage it in the most professional way possible when it does inevitably happen, using Listening, Empathy, Dignity and Respect as key skills in de-escalation.

Your staff who sometimes work with people who carry a higher risk of physical assault need a robust but appropriate system of physical skills to disengage from simpler assaults and perhaps also to protect themselves from serious violence in high-stakes personal safety scenarios.

Your community-based teams who work alone or away from a fixed base need to know how to quickly identify and prevent personal safety risk and also have the attitudes and habits which can get them out of those situations as swiftly as possible if they do happen when they are working alone.

Your teams already use words, behaviour and restraint -reduction plans to minimise the risk that physical holding or control and restraint skills will be needed either for clinical reasons or in response to spontaneous violence, however last-resort skills must be both compassionate and effective in reducing risk.